Renfrewshire Before the Days of Modern Medicine and the NHS: Part 1

- Gavin Divers

- Sep 4, 2024

- 4 min read

My grannies (Ina and Elizabeth) first discussed this subject in the mid-1980s. It’s important to note that these memories were written 34 years before COVID and what followed (the New Royal Alexandra Hospital in Paisley had recently opened). Although predominantly a Renfrew story, Paisley is mentioned many times throughout the memoir.

It’s a long story, so I have split it into four posts (this one takes us up to 1930). To remove any of this story would be a disservice to my grannies and to those who lived through these times. It’s not a cheery story, but it was their reality and showed their bravery.

We were born during and just after "The Great War" (1914-18). It was a dangerous time to be alive. For every ten babies born in Renfrewshire, only 3 or 4 would see their adult years. In our own families, no less than six children died in infancy.

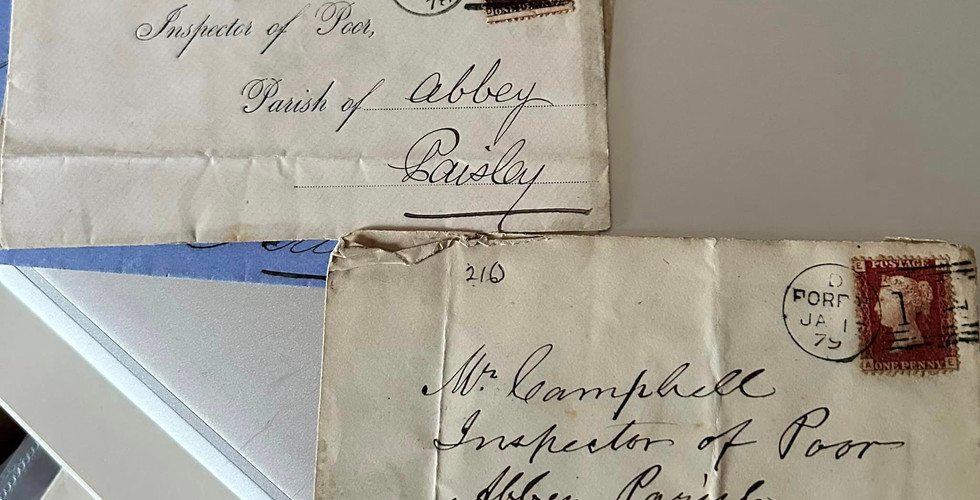

Less than 90 years prior, the town had been devastated by a cholera epidemic (there is a mass grave at St James in Paisley). In those days (1832), Renfrew was a sleepy, affluent weaving town. There were no shipyards or industry. We lived in thatched cottages, shared water taps, and had poor sewage systems. The prosperous town of Renfrew and its much larger neighbour Paisley soon ran out of burial space.

Why, though, in the 1920s was infant mortality so high? There were many reasons. Healthcare was poor and expensive. Modern vaccines and medication were many years in the future. The doctor and dispensary, as we called the chemist, sat in the middle of the town as it had for centuries.

Indeed, my sister’s first paid job at 15 was to sharpen and sterilise the needles (a vaccine in those days was agony) for the few vaccines available (smallpox). If you did not have the money to pay for this vaccine, then an application was made to the parish to cover the fee. Refusal was not an option. There was no Scottish ambulance service. Hospitals existed, of course, but these were NOT free. The threat of the poor house was still a reality in 1920.

Both our fathers were skilled workers, and they paid into their employer’s health schemes. Rarely did this include wives and children (pennies were kept back or neighbours had a collective to pay for doctors' visits). Birth control was not accessible, for this too was decades away. Midwifery was recognised and registered in 1916, but like doctors and incubators, it was beyond the means of many. My mother (Elizabeth) was a lady many called upon. A baby born early would be placed in soft cotton wool, in a shoebox close to the fire. Fed every two hours their mother’s milk from a medicine dropper, for they could not suck. I still see the image (Ina) of the little baby my mother and father took in, her mother having died across the landing of the house on Paisley Road. She survived against amazing odds. My father could fit the whole child in the palm of his hand.

When a baby arrived, everyone worked together to help the mother in her “lying-in” period. Neighbours cooked meals, washed clothes, and did household chores. Of course, we now know this “lying-in” period was the worst thing. “White Leg” (blood clots) and childbed fever claimed many. We didn’t understand that a new mother should get up and move around to prevent this.

My mother’s other job was to prepare people for burial: men, women, children, and babies. Do not think that because death was so frequent in 1920, our hearts didn’t break the same as today. It was important, and just, to give our loved ones a good send-off.

Memories that are vivid: My brother getting badly injured by a horse at the Renfrew Town Hall—tormenting it, no doubt—for it bit a large chunk of his bottom. Henry was always up to mischief. My mother met with the hospital administrator at Paisley to discuss the cost of his inpatient care. Many hospitals existed: “The Merry Flats” Poor House, which became the Southern General Hospital in 1923, the Royal Alexandra Infirmary (1900), the many infectious disease hospitals in Paisley (just by the Abbey), the village of Linwood, the Braes, Millport, Bute—too many to remember. TB, polio, scarlet fever, diphtheria. There were no such drugs as antibiotics, insulin, blood pressure medicine, or adrenaline in Renfrewshire’s dispensaries or hospitals. My little friend had injured his leg on rusty farm equipment while playing. No tetanus injections in those days—“lockjaw” was a horrible way to go.

Winter months would be a worry for the lungs. The summer months always brought the threat of polio. We had a basic understanding of germs, but polio did not discriminate between the rich and poor. Often, in the damp colder months, the cobblestones would have a strange green luminous glow—the infected spit of poor souls, for we did not have paper hankies back then.

There was also the threat of the poorhouses. My father spent six months in the Paisley Children Poorhouse, aged just 10 (there had been several bad harvests at the end of the 19th century). That memory stayed with him for all of his life. If people had no family, then this was all there was to keep them from starving to death. The Royal Alexandra Infirmary Poorhouse existed until the 1970s. Many poor souls would will themselves to die rather than transfer to “The Castle.” This was where the poor were taken once they recovered enough to leave the wards.

Written by Jillian McFarlane

Extract from the memories of Elizabeth Davidson McCrone, Ina Shirlaw Meek Payne, and the information they collected from The Renfrew Historical Society.

Comments